Writing Decolonial Poetry for Ea

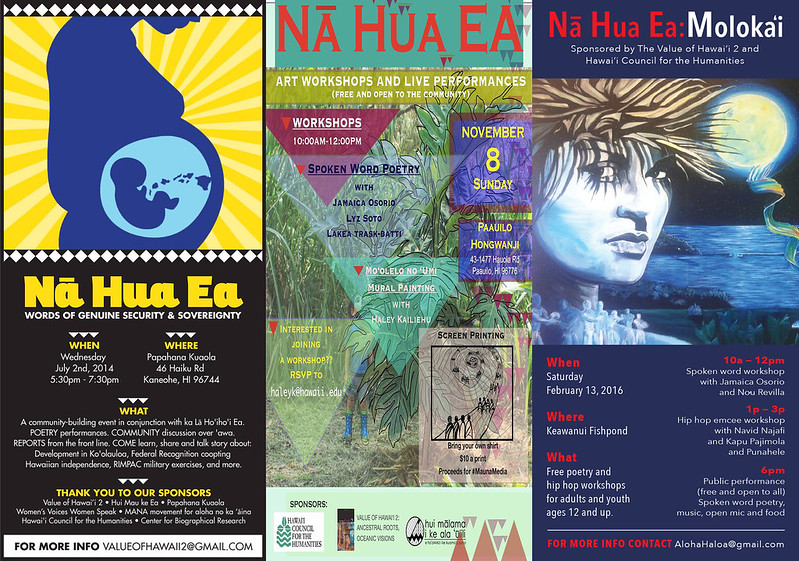

We held the first “Nā Hua Ea: Words of Genuine Security and Sovereignty” in July 2014 in Waipao, Heʻeia, Oʻahu. Over 100 of us gathered together in the large green-painted warehouse at Papahana Kuaola listening to speakers talking about the issues that the people of Hawaiʻi face: increasing US militarization of sacred lands, Department of Interior hearings about federally recognizing a Native Hawaiian government, plans for development of rural areas on the North Shore, state violence against young Hawaiian men and the families who grieve them.

In response to these collective traumas, people shared poetry and music and oli—crying for new pathways learned from the plants, shouting unashamed anger and reclamation of ancestors, laughing at the contradictions of US warships, singing to ancestors and new babies—telling futures of genuine security and genuine sovereignty. As the rain poured on the tin roof overhead, as we stood in a circle singing mahalo to Aunty Terri-Lee Kekoʻolani for her great contributions to the present aloha ʻāina movement, we felt deep aloha and hope tingling between us in all of our powerful genealogies. We are rising.

In the month leading up to this gathering, about twenty activists, writers, and artists had gathered together periodically to learn and discuss ideas of “ea,” to write and draft poems together, and to introduce ourselves humbly to the ʻāina who was to host us on the day of our performance. Over tables of shared food and small children coloring on the floor in our house in Pālolo, or sticky with rich dark mud and cooled by the refreshing headwaters of Haʻakōlea in Waipao, we took risks, shared our difficult and different paths, and let our friendships push us into braver political and artistic acts than we would dare alone. As Kānaka, as local Japanese, Filipino, Okinawan, Haole, Chamorro, Sāmoan, Chinese, Korean, we declared our commitments to a sovereign Hawaiʻi nei and to each other. We are rising.

Since 2014, we have helped to organize additional Nā Hua Ea with huiMAU in Hāmākua, with Nā Mea Hawaiʻi in Honolulu, with Hui o Kuapā and Molokainuiahina Mural Project at Keawanui Fishpond. Here we practice “the safety to be unsafe” in our poetry and music workshops. Guided by artist facilitators, we explored family, love, history, fears, food, health, gender, violence, legacies, dreams, memory, laughter, colors, rhymes, and integrity. Mahalo Lyz, Jamaica, Noʻu, Punahele, Navid, Haley. Here we practice mālama ʻāina on revolutionary kīpuka that are growing day by day. Guided by fierce aloha ʻāina, we planted names and kalo, cleared tough buffalo grass, marveled at ancestral abundance, learned about the relationship between wind and sea cliffs. Mahalo Noʻeau, Haley, ʻIlima, Maile, Hanohano. Love, Risk, Sweat, Humility. These are our creative sovereign practices together.

Caption: left and right flyer designs by Culture Shocka, right image by Molokainuiahina Mural Project, middle by Haley Kailiehu

Caption: left and right flyer designs by Culture Shocka, right image by Molokainuiahina Mural Project, middle by Haley Kailiehu

My own ancestors came to Hawaiʻi as Japanese sugar plantation workers to Puʻunēnē, Maui, as Okinawan farmers and peddlers to Kāneʻohe, Oʻahu, and from Guåhan over bridges of American militarization. As a typical local immigrant, newly middle-class family, they struggle to understand my aloha for Hawaiian activists and issues, my work as a friend in community organizing for decolonization and demilitarization. They donʻt understand why I am so committed to helping “them,” or how local non-Hawaiian communities have common cause with political battles over land, resources, and sacredness they see as being “Hawaiian issues” they have no business dealing with.

Unjun Wannin, Iya-n Wannin, Kanpo nu kwe-nukusa.

You and I have become scrap leftovers of the battleships.

–Uchinaaguchi lyrics of Kanpo Nu Kwee Nukusaa, by Koubin Higa and sung by Deigo Musume. Translation shared by Ukwanshin Kabudan.

As a poet, teacher, daughter, granddaughter, and community organizer, I have learned that activism demands feeling beyond binaries of us versus them. This does not mean we erase our differences for the promise of some willfully ignorant peace, or try to calculate and equalize our rights or our trauma. Activism means we are committed to learning about and honoring our connections. The powerful ʻāina, kai, and kānaka of Hawaiʻi have fed and cared for my family and loved ones. I am indebted to you. When I fight for pono futures for Hawaiʻi, I fight for a better dream for everyone I love. Because of you, I am. Activism is love and commitment over generations of memory.

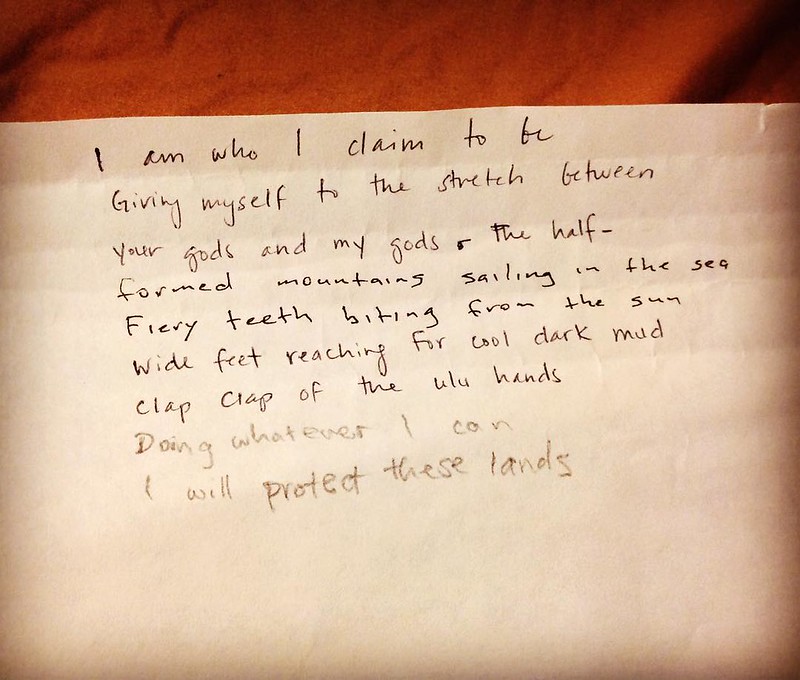

Caption: Group poem from Nā Hua Ea 2016 on Molokai, exercise facilitated by Navid Najafi

Caption: Group poem from Nā Hua Ea 2016 on Molokai, exercise facilitated by Navid Najafi

In Kanaka ʻŌiwi Methodologies, Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua reminds us that “ea is an active state of being. Like breathing, ea cannot be achieved or possessed; it requires constant action day after day, generation after generation” (9). To reconnect to our genealogies of ea, we need to grab our histories more tightly. Here, we have ongoing histories of devastation of land and waters for profit, racist and genocidal legislation that disconnect people from home, culture, and each other, and betrayal of sacred connections for development and progress. These are our histories we must face in order to refuse further complicity in the destruction of Indigenous pasts and futures. In order to reclaim our courage and wholeheartedness. To commit to each other’s aliveness together.

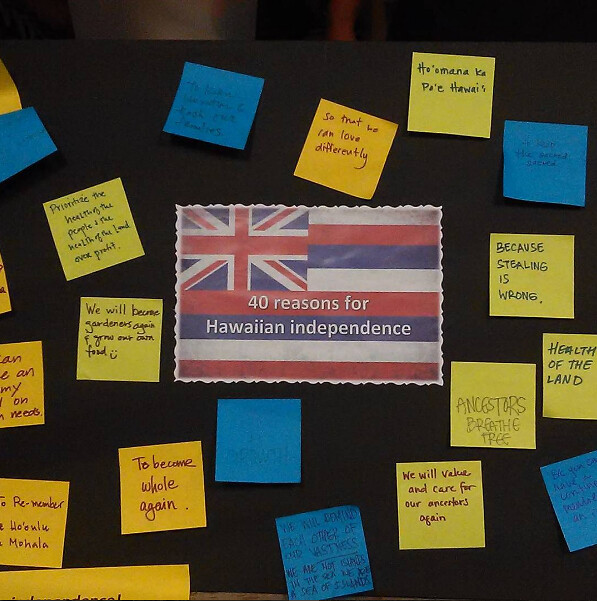

We have histories of pledging allegiance to the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, of striking together against plantation interests, of rebelling and being arrested for our Queen, of attending funerals of our young men, of occupying military training grounds, of blockading roads to prevent hotels and the diversion of stream water, of planting kalo, of fighting for Hawaiian immersion schools, of caring for each other’s elders and children, of refusing to bulldoze bones, of testifying that sacred places are not wastelands. These are our radical genealogies of kuleana that we must remember in order for ea to flow strongly again—where stolen governance, land, and water are restored to Kānaka ʻŌiwi. Where we can learn to “love differently.”

Caption: Photo taken by author at Nā Hua Ea 2015, Papahana Kuaola

Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada shared with me this definition of ea that grew from his own experience writing and performing poetry at our first Nā Hua Ea. Ea as “the desire, the reciprocity between people. That moves people to do things. That moves people to get involved and to work on the land or to learn Hawaiian or to learn the stories….A lot of times I feel people see responsibility as shackles. Like this extra weight that you get put on you. And in certain ways it can be. But I feel like the real ea is when you see that you are in this web of responsibility, but you can also draw sustenance from it. And help other people with it. Because kuleana is a responsibility but it’s also a privilege. So you awaken people to that privilege of that connection. ʻCause those are not shackles, they’re connections….I think that’s one of the most amazing things about seeing those connections, with that idea of ea. That’s what our community is. When people are so moved by their love for something that they stand up against this whole training that they’ve had for their whole life.”

Because poetry dares us to imagine impossible things, writing poetry together has been an important decolonial community practice. On June 28th of this year, a few of us poets activists students teachers mothers daughters got together to write in preparation for this yearʻs Nā Hua Ea. Our workshop methods were inspired by a poem that Noe and Bryan had written and performed for the 2016 Native American and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA) conference in May, where they wove together lines from other poets, ancestors, their own naʻau, and testimony given at the 2014 Department of Interior hearings across Hawaiʻi; aloha ʻāina past and present.

one by one

strand by strand

we become the memory of our people

and we still growing.

–From ‘Īmaikalani Kalāheleʻs poem, “Making Rope,” in Noe and Bryanʻs presentation, “Remaking the ‘Aha: Braiding Strands of Hawaiian Self-rule, Genealogy and Ritual”

That evening, Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea organizer Noe invited us to time travel, listening to two aloha ʻāina speaking to crowds at ʻIolani Palace in 1982. “If you see that something needs to be done, do it,” said Aunty Judy Napoleon. “We are an alternative,” said Haunani-Kay Trask. In these videos, they are so vibrant we cannot look away. We thanked these kumu, silently. We circled around Aunty Terri, she laughed and told us true things. How women fought to lead, not just cook.

We gathered in the cool pathway of Līlīlehua rain, in the Osorio hale in Pālolo. We thanked poet facilitator Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio for her family being puʻuhonua to us. Another poet facilitator, Noʻukahauʻoli Revilla asked us to think about ea as sharing stories. “Weʻre not hoarding.” She offered armfuls of books, we went around and shared other songs, prayers, photos, grandparents, remembered words, and the words that remembered us.

[I brought the lyrics of Kanpo Nu Kwee Nukusaa. I brought a memory of war in Okinawa, of devastation that feels impossible to heal—as the US military and Japanese government moves to build a new base, as coral reefs and rich bays will be dredged, as blockading kūpuna are removed forcibly by police, as another young woman is raped and murdered.]

Wakasaru tuchine ikusanuyu, wakasaru hanan sachi yu-san `yan, gwansun, uyachoden, kanpo shageki nu matuminati. Chirumun, kwe-mun, muru neran, su-ti chya kadi kurachanya.

I was young when war came, our youth was interrupted. Our houses, grandparents, parents and siblings, came the rain of bombs and artillery from the ships destroying and making the land unrecognizable and hard to look at. Our clothes, food, everything gone, we had nothing so we ate the poisonous seigo palm.

–from Kanpo Nu Kwee Nukusaa

She asked us to compose lines inspired by the aloha we felt now and the aloha we carried.

We scattered to the night, chewing poke and pita chips, pizza. We wrote on index cards, sometimes a phrase like: “defending life with the spear of memory.” sometimes a genealogy. Sometimes one word, like “freedom.” Some of the words hurt, some of the words were ripe fruit for long journeys. We kept some and gave up many of our words to each other.

I kept the English translation: “You and I have become scrap leftovers of the battleships.”

We gathered the driftwood and the riches, and sat on the floor, on lawn chairs, we hid in corners. We touched these new words carefully—some ours, some of our friends. We turned them and spun them and danced with them and didnʻt know fully what to do with them. We gathered in the house.

Unjun Wannin, Iya-n Wannin, Kanpo nu kwe-nukusa.

You and I have become scrap leftovers of the battleships.

We are not apologizing for our poems, Noʻu directed us. We were nervous. We were eager. We read with each other. And then we talked about what we heard. Instead of saying sorry, we said thank you.

We heard surprise, delight, wonder. We heard that our manaʻo mattered. When we gave beautiful ideas away, they grew in unexpected directions. When we gave sad ideas away, they were liberated. We forgot single authors. We forgot ownership. Instead, we saw “the reflections of ourselves in each otherʻs expressions.” Our words were held, and we knew we were not alone. This is some of the manaʻo shared by Bryan, Kapili, Hina, Noe, Laʻi, Aunty Terri, Noʻu, Jamaica, me, Akta, Reyna, and Emily. Mahalo to you.

I would like to thank our youngest poet that night, Laʻilaʻikūhonua Kaʻōpua-Winchester, for teaching me about ea. The Bruno Mars song lyrics she brought to share with us helped me rise out of battleships, caves, a war-torn present. Helped me emerge from stories of depression, despair, and disconnection. From feeling helpless. She helped me write this poem instead:

Because of You, I Am

For Laʻi

When we are called to help our friends in need

You and I have become leftovers

You and I have become spears

When we are called to help our friends in need

You and I are the placenta

You and I are the naval cord

You and I can hear our ancestors crying

When we are called to help our friends in need

You and I are 400,000 feathers

You and I will be the site of memory

You and I will hear our ancestors being born

Nā Hua Ea: Sovereign Words will be held Saturday, July 16th, 2016, from 5 – 7 pm at Papahana Kuaola. We hope you can make it!