“Holderness coastal erosion” by Ian Dolphin, used via CC 2.0

Building Government on Flimsy Foundations: Redesigning Constitutional Creation Processes

Hoʻokahua ka ʻāina, hānau ke kanaka.

Hoʻokahua ke kanaka, hānau ke aliʻi.[1]

The land creates the foundation upon which the people are born.

The people create the foundation upon which the chief is born.

–Ke Kaao Hooniua Puuwai no Ka-Miki, 1916

Genuine nation-building must happen from the ground up. Instead, Naʻi Aupuni is attempting to slap a government together while neglecting basic principles of good governance: inclusiveness, transparency, and education. The convention, or ʻAha, that Naʻi Aupuni is convening begins today at the private Royal Hawaiian Golf Course, and both private security and HPD will be there to keep people out. Apparently unaware of the multiple layers of irony, Naʻi Aupuni issued a press release stating that: “In order to foster a good dialogue, at this time the ʻaha discussions are not open to the public or the media.”

According to another Jan 30, 2016 memo from Naʻi Aupuni to ʻAha delegates about “safety & security”: “Only registered participants will be admitted into the meeting rooms. Others may not remain on the property. Bags may be inspected, and anyone participating in the ʻaha, including staff, may be scanned with an electronic scanning device.” Claiming to offer aloha to expected protestors, Na‘i Aupuni representatives have designated a small area for protesting outside the golf course’s security gate, “which is located roughly a mile from the facility itself.”

Throwing a further scrap to the people, Na‘i Aupuni has offered to televise the scholarly lectures that the 154 registered ‘Aha participants will see in person. Wow, mahalo for that. Organizers seem to think an hour and fifteen minutes is enough to teach participants and the viewing public about “Constitution Building: Process and Contents,” one of the five lectures they have planned.

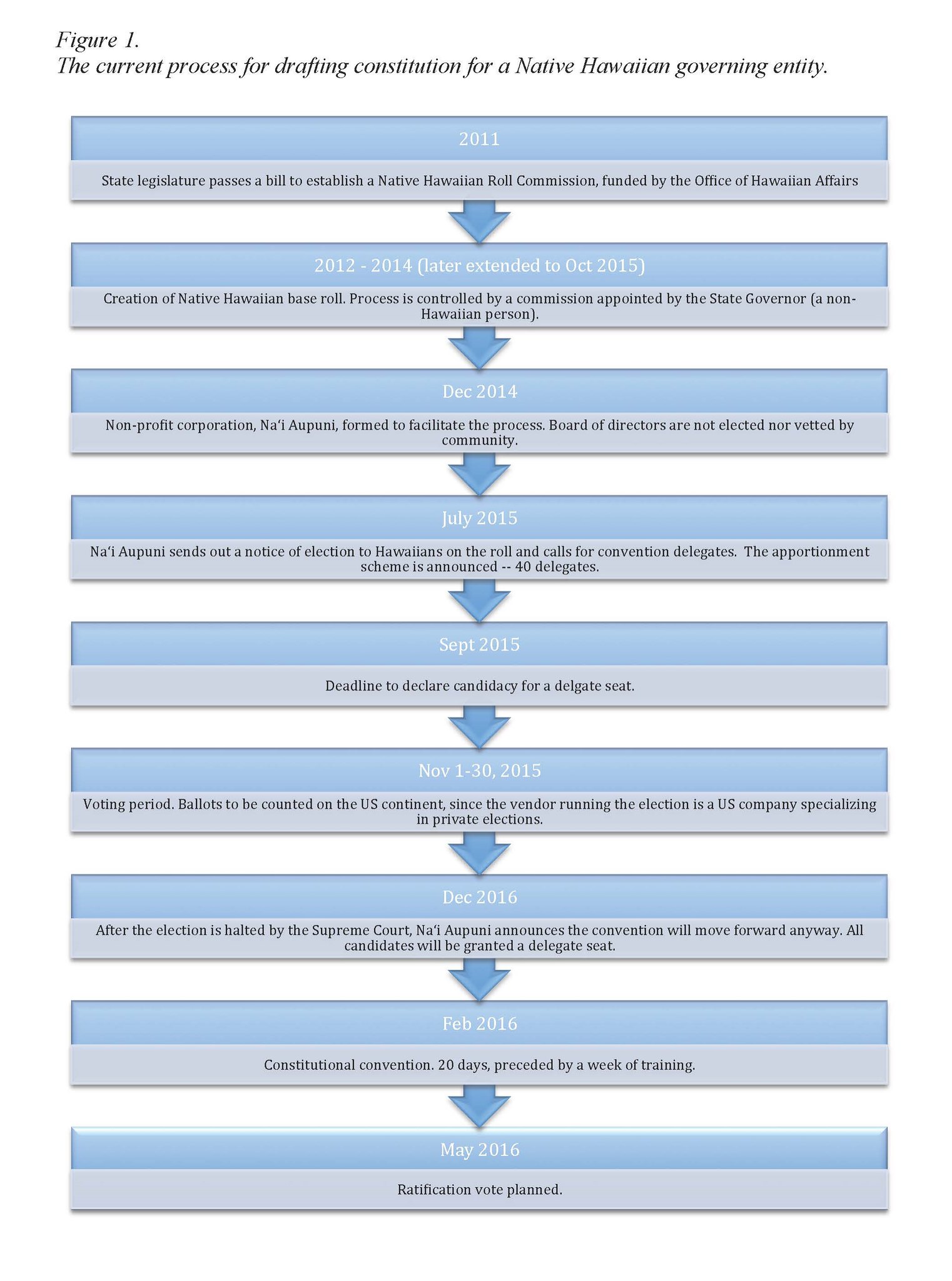

Naʻi Aupuni’s process has been plagued by a top-down approach to government-building from day one. Here is a quick recap: In 2011 state legislation, Act 195, established a governor-appointed Native Hawaiian Roll Commission. The commission hired as its executive director the former CEO of OHA under whom federal recognition had been vigorously pursued. Amidst controversy and protest, the commission took the next three years to compile a roll. While the Kanaʻiolowalu process garnered the interest of 40,000 Kānaka, the commission was unable to meet its target goal so it lobbied the state legislature to pass another measure, which moved names from previous initiatives to establish databases of Native Hawaiians. Approximately 71,000 names were moved from the “Kau Inoa” and “Operation Ohana” lists to the Native Hawaiian Roll, without the consent of the individuals on the list. The roll was then handed over to a newly-formed private, non-profit entity, Na‘i Aupuni. Na‘i Aupuni is led by a board of five non-elected volunteers. Their board meetings are not public. OHA trustees selected Na‘i Aupuni to manage the funds and hire the vendors to run the subsequent election and convention process. Both OHA and Na‘i Aupuni pushed a ridiculously tight timeline: the notice of elections, declaration of candidacy, campaigning process, election, convention, and ratification vote are all supposed to take place within the span of less than one year.

One year? Yes, one year. When I shared this process with participants in a “Constitutions of Indigenous Nations” seminar at the University of Arizona last month, they were blown away by the short timeline. The seminar included constitutional law scholars, tribal leaders, and members of various Indigenous nations, some of whom are federally-recognized and almost all of whom had been through constitution-creation or revision processes within their lifetimes.[2] Their reactions confirmed to me the concerns that numerous Kānaka have been raising over the past few years. The conversations inspired me to compose one possible response to a question that at least one OHA trustee has thrown at critics of the roll: “well, if you don’t like it, what’s your plan?”

What others kinds of processes can we imagine that would be better than the one unfolding now? The rest of this post is a humble contribution to existing efforts to envision and create better processes for engaging a broad range of Hawaiians in planning and rebuilding a national government. The plan I outline below is not meant to be the answer. It is meant to help expose the inadequacy of the Na‘i Aupuni process while opening space for more plans and processes to be debated and deliberated amongst the lāhui Hawai‘i. Some of these conversations are already happening on various islands. Before anyone at the February ʻAha, or any other gathering of Hawaiians intending to implement a government, gets to the point of proposing, ratifying or implementing constitutions, we need to design better processes.

A Redesigned Constitution Creation Process

Basic Principles:

The proposed process was designed with six basic principles in mind:

- Inclusiveness, with many opportunities to opt-in and opt-out.

- Education and informed participation. Providing spaces and time for people to learn necessary information, build relationships of trust, have critical conversations, and test out ideas is absolutely critical to the long-term success of the process and product.

- Transparency and documentation. All stages of the process should be open. They should also be thoroughly documented and that documentation archived for public access at any and all times.

- ʻO ke kahua ma mua. Building from the ground up. The process builds on the base of an informed people, then coalescing at the local and regional level, and finally at a national level.

- “Kūlia i ka nuʻu.” Striving for excellence. Process and authentic outcome are more important than an arbitrary timeline. We want to do it right, not fast.

- Internal focus. Issues of recognition, whether state, federal or international, are understood as external issues that shall be dealt with in time. Before dealing with the question of recognition by any other nations or governments, we will first focus on what government best serves our purpose of thriving as Kānaka ʻŌiwi into the future.

It is also important to emphasize that a constitution does not just have to be a formal written document. The word “constitution” conjures certain archetypes in peoples’ minds. While constitutions might include a single, formal written document, they can also include multiple written and unwritten, formal and informal sources of law. More important than form is a constitution’s function: to express the relationship between a people and their government and to set out the scope and structure of that government. The proposed process below assumes that one goal might be to produce a formal written constitution, but such a document may be accompanied by other graphic or oral forms expressing the intent, guiding values, structure and functions of a Hawaiian government.

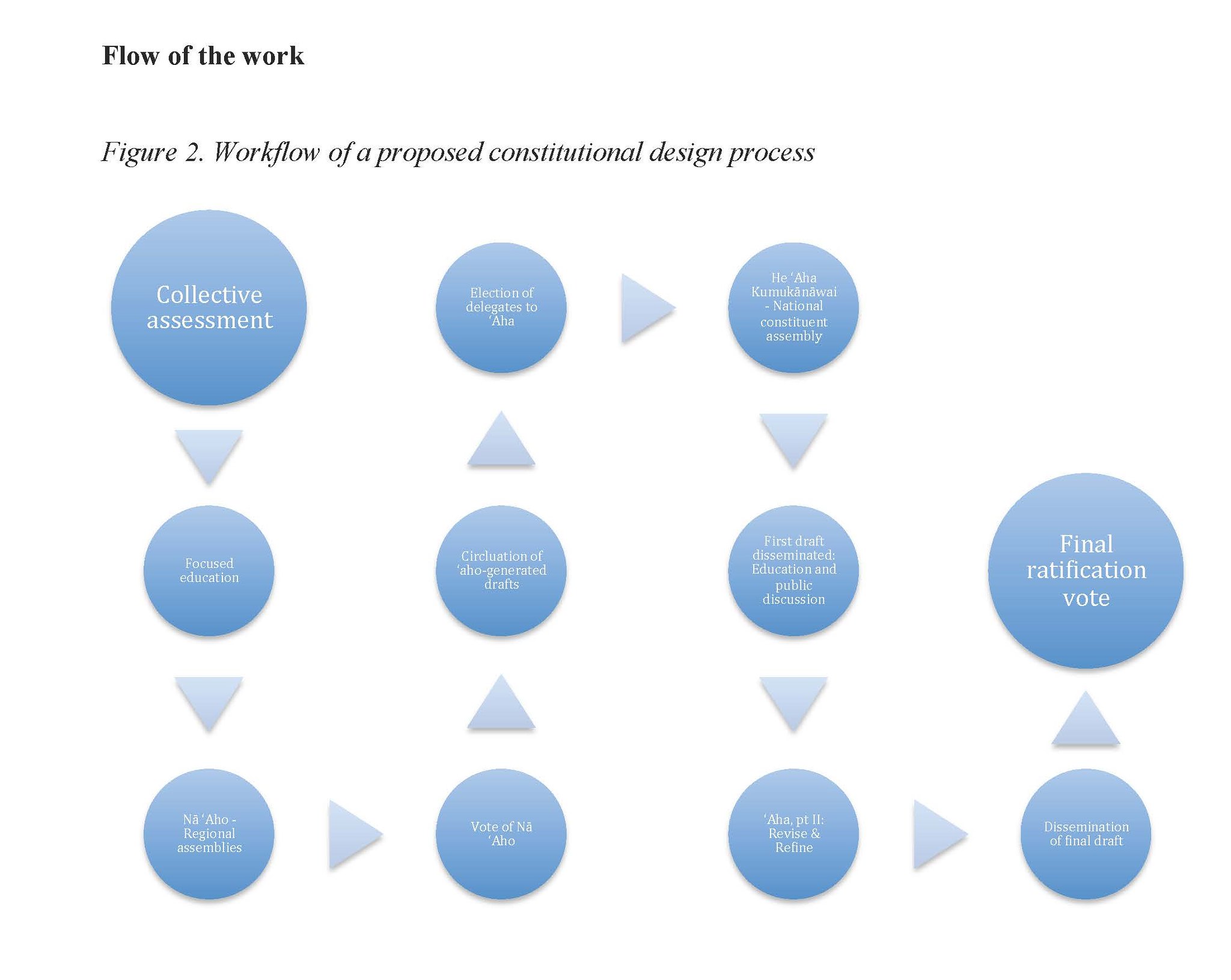

Flow of the work

The process could flow through multiple stages. The graphic below represents the way this proposed process could be purposeful and directional but non-linear. Imagine a waʻa tacking back and forth against the wind, or a spiral moving forward but circling back again and again to ensure inclusion, education, and flexibility. It is assumed, but not prescribed here, that prayer and ceremony would be important at various points along the way. Proposed stages are described in detail following figure 2.

- Collective assessment

The collective assessment should be as broadly inclusive as possible. People can choose whether or not to participate, and they can end their participation at any time. The collective assessment would include both face-to-face “town hall” or “listening session”-type meetings, and this phase of the process would also utilize an array of online platforms for engaging people who cannot physically access such meetings.[3] Whether in person or online, the collective assessment is organized around four key questions:

- Who are we? Sub-questions include: Who shall be included in the political community? Kānaka Maoli exclusively? If not Kānaka exclusively, do Kānaka Maoli have a unique standing? Is residency necessary? What about Kānaka in the diaspora? Might we think about multiple layers of citizenship?

- What do we need to sustain us? In other words: What does the “we” defined above need in order to survive as a collective for generations into the future?

- What existing community-level governance is already working?

- What is most important to you about the process of how we move forward in building our government?

The responses to these key questions would inform the following phases of the process.

- Focused education

While this is listed as phase 2, this educational effort could actually be overlapping and in conjunction with the collective assessment phase. This phase of focused education would aim to do at least three things:

- Provide information from respected experts on governance challenges and collective strengths. What do we know about traditional Hawaiian governance—from Kumulipo to Kingdom? What are the key issues that will shape our futures? Create a video archive of respected experts, such as kūpuna, cultural practitioners, scholars, speaking about these and other key issues that will impact Hawaiian governance into the future. Additional topics might include food & agriculture, fresh water, fisheries, energy, education, economics, climate change, etc. The video archive would be fully and freely accessible online. It need not only be monologues, but could also include debates, panel discussions and participatory webinars.

- Offer face-to-face meetings, workshops, and courses in political design and comparative constitutions. A suite of workshops or short courses could be offered in communities. People would be able to look at constitutions from various nations, including the constitutions of the Hawaiian Kingdom and more recent constitutions that have been drafted by Kānaka, such as the Ka Lāhui Hawaiʻi constitution.

- Share back findings from the collective assessment phase. This sharing could include open access materials online (videos, infographics, etc.), as well as community presentations.

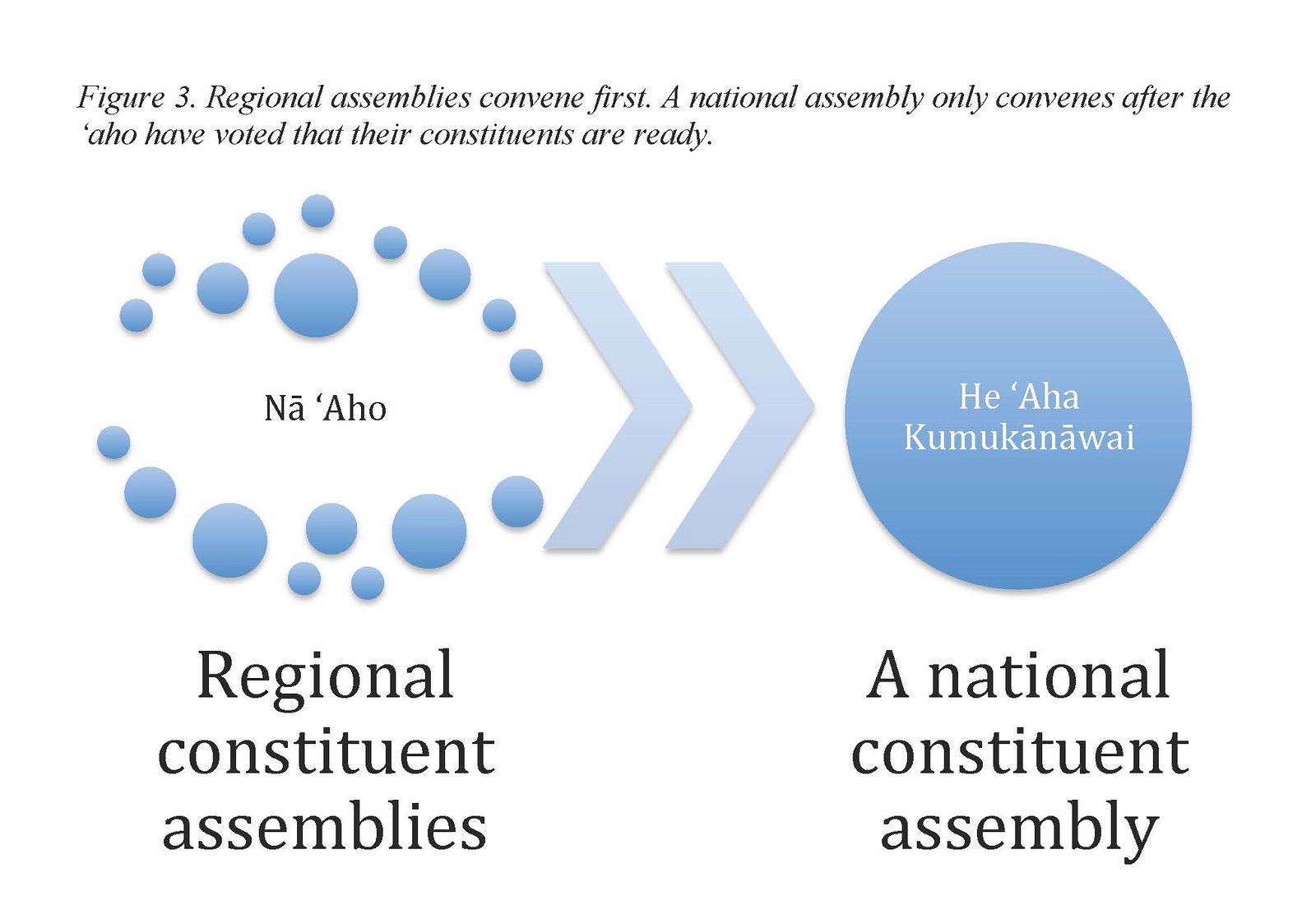

- Nā ʻAho (The Strands): Local and Regional Assemblies

After the first two phases of assessment and education, people will first begin convening for decision-making at the local or regional level, in ʻaho, or strands (see Figure 3). In addition to geographically defined assemblies, there could be at least one ‘aho that convenes and conducts its proceedings exclusively in the Hawaiian language. The geographically-defined ‘aho may choose to proceed in any language that suits their constituents. Each ‘aho will determine its own process for deliberation and its own leadership structure. Any lists of membership would be kept at the local level. People should be able to sign on or opt-out at any point in time. Each island would have at least one ʻaho. Assuming that Kānaka Maoli in the diaspora are included in the political community, there could be ʻaho on the US continent, especially in areas with large numbers of Kānaka, such as California, Washington, and Las Vegas.

-

- Vote of Nā ʻAho

Once Kānaka have organized at the local and regional levels into ʻaho, a vote would be posed of the ʻaho asking: “Should we convene in a national assembly? And should the national assembly take on the kuleana of drafting a constitution?” If the majority of ʻaho vote “no,” then the process would stop until such time as the majority of ʻaho feel that the time is ready to convene at the national level. The local/regional ʻaho could remain active and could continue to be avenues for engaging Kānaka in political organizing at that level. Their function would be to build a strong base at the ground level and to advocate for the needs of the members of their communities.

-

- Generation and circulation of ʻaho-generated drafts

Assuming that the vote for a national convention is positive, nā ʻaho would begin the process of generating and circulating draft constitutions among their own members and then the wider political community. This way, the creation of draft constitutions is not limited to a small, tightly-controlled body of experts. A central organizing committee can play a neutral role in helping to maintain a central hub online so that all draft constitutions can be accessible to the public. This hub could resemble Reddit, where people can vote certain drafts of constitutions, or online commentaries on various constitution drafts, “up” and “down.” Online participation in such forums need not be limited to people on a set list or “roll,” because they are simply forums for discussion and not decision-making mechanisms.

-

- Election of delegates to ʻAha

The election of delegates to a national ʻAha would be run by an independent committee comprised of representatives from various ʻaho and with neutral international observers present at all phases of the election. It is only at this point that a voter registration effort would need to take place. Earlier phases have assured that people are informed and have had numerous opportunities to opt-in to the organizing that they see unfolding. Assuming that the political community includes Kānaka Maoli who are not in residence in Hawaiʻi, a possible apportionment should take into consideration:

-

- Unique geographies. Each island within the Hawaiian archipelago has unique needs and should get its own representation.

- Some seats should be based on the distribution of the population of the political community. This might include specific representation for Hawaiians in the US and other countries. However, population should not be the sole factor in apportionment.

- The elections committee should also consider how to assure representation from various areas of Hawaiian cultural practice, such as waʻa, hula, mahiʻai, lawaiʻa, lāʻau lapaʻau, etc.

With nā ʻaho as an active base and with draft constitutions circulating amidst the public, an election process would begin with people declaring their candidacy. An adequate campaign period would be essential, so that candidates could participate in public debates, engage in on-going public discussions about draft constitutions, and better understand the needs of their constituencies. Transparency in campaign contributions and spending would be mandatory for all candidates.

-

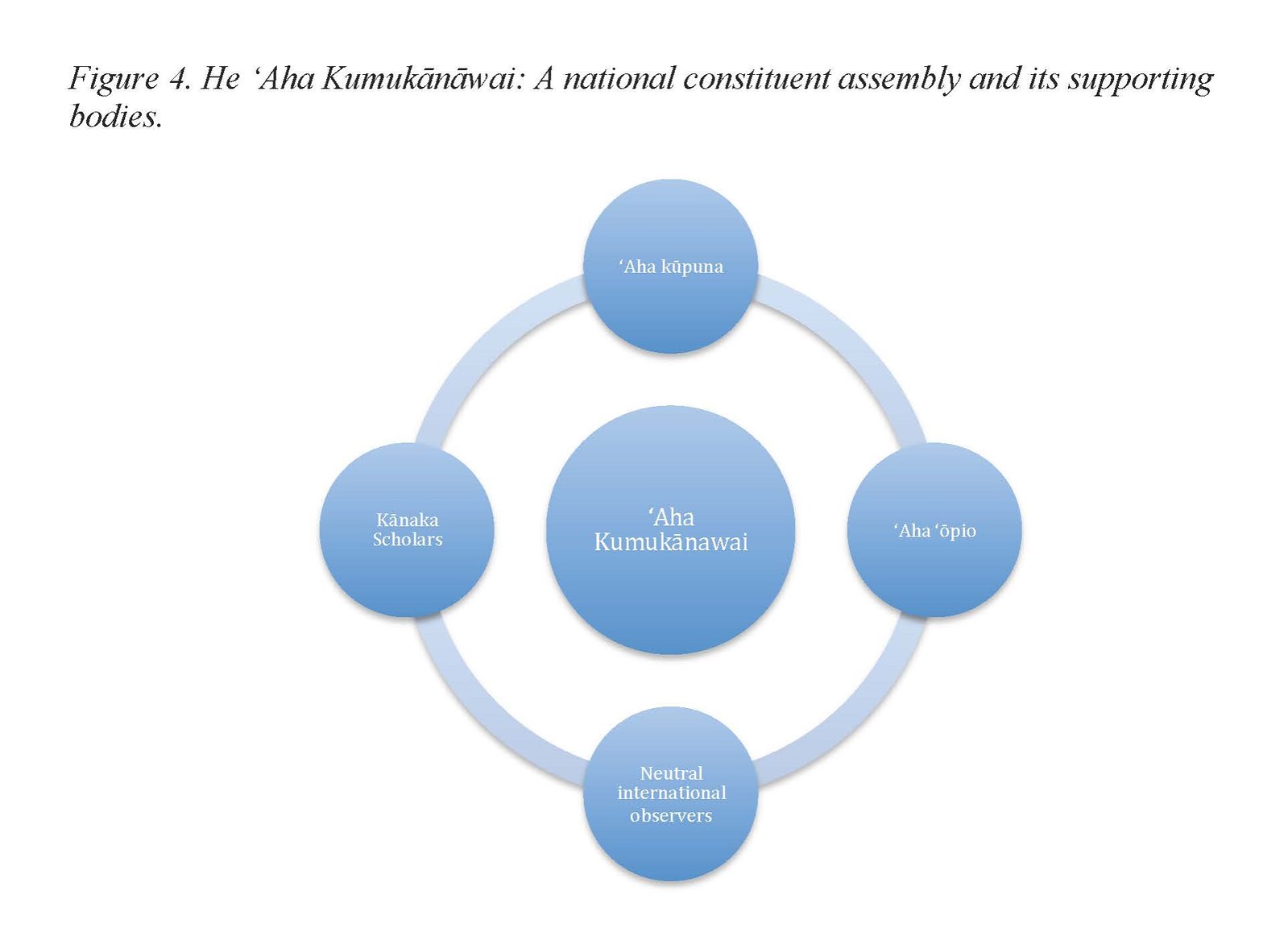

- He ʻAha Kumukānāwai – National constituent assembly

The national constituent assembly, He ʻAha Kumukānāwai, would be comprised of the elected delegates. This ʻAha would be the primary decision-making body, and it would have the authority to create a constitution for a national government. The ‘Aha would take the drafts generated at the ‘aho-level into serious consideration as they deliberate on a unified document. This could also include earlier constitutions of the Hawaiian Kingdom. It is highly recommended that delegates “test out” different draft sections against scenarios based on the real world experiences of other governments (such as issues related to jurisdiction, dispute resolution, natural resource management, etc.). This could be done in role plays or other engaging formats, so that delegates could really see how different sections would work in practice and also anticipate what kinds of supplemental laws and policies might need to be developed after the constitution is ratified. He ʻAha Kumukānāwai would be embraced by four councils that would serve in an advisory capacity: an ʻAha Kūpuna, an ʻAha ʻŌpio, a council of Hawaiian scholars, and an international group of neutral observers (see Figure 4). The first two—the elders’ council and the youth council—would have parallel conventions and could put forward proposals to the ʻAha Kumukānāwai or public statements to the broad citizenry.

A team of scholars, journalists and filmmakers would help to thoroughly document, in video and written forms, all of the deliberations. Members of this team would also be asked to help provide day-by-day reporting out to the public about the deliberations. This could include livestreaming, real-time tweets, and daily blogposts.

- First draft disseminated: Education and public discussion

After the ‘Aha Kumukānāwai agrees upon a first draft of the constitution, it would go on recess, and a new round of education and public discussion would begin. The sole purpose of this round of education is to make sure the citizenry understands the constitution that has been drafted and has time to provide feedback before the final ratification. During this period, delegates would be expected to return to their communities and participate in face-to-face town hall meetings, coffee hours, and other events to inform, to listen, and to discuss. Additional forms of online civic participation can be used to generate rigorous public discussion about the proposed constitution. Face-to-face workshops might also ask citizens to test the proposed constitution against scenarios based on the real world experiences of governments (such as issues related to jurisdiction, dispute resolution, natural resource management, etc.). Specific groups could be convened to get their feedback based on their particular areas of expertise, such as in legal, economic and cultural dimensions. During this period, voter registration could be re-opened, such that people who previously did not or could not register would be able to opt-in.

- ʻAha, pt II: Revise & Refine

With all of that rich public dialogue and targeted feedback, the ‘Aha would reconvene to make final revisions to the constitution. Again, it is highly recommended that this final gathering include testing the document against contemporary real world scenarios, so as to assure the strength, cultural integrity and flexibility of the document when dealing with issues such as jurisdiction or dispute resolution. The ‘Aha would have previously decided how many votes would be needed to move the constitution on toward ratification by the full electorate.

- Dissemination of final draft

Once the ‘aha agrees upon a final draft, it would end its proceedings and the final draft would be circulated out to the public. This education phase would focus on assuring that the public understands what the final draft says and what ratification would mean.

- Final ratification vote

The final ratification vote is a yes-or-no vote by the electorate to accept the constitution.

- Education and Implementation

The process does not end with ratification. Once again, it is important to circle back to the public for education about what implementation means and how people can stay involved in their government. Then the hard work of implementation begins.

Final Thought

What I have outlined here is just one possible process for creating a constitution for a Hawaiian national government. It is far lengthier and more involved than the process we have seen unfold under the control of OHA, Kana‘iolowalu, and Na‘i Aupuni. It does not address some important questions about how such a process would be funded and staffed. However, I believe that if the millions of dollars that have been poured into lobbying for federal recognition, marketing for the roll, and contracts for the upcoming ‘aha had instead been put into a more community-based, education-oriented process from the beginning, we would be much farther along than we are now. If we work from the ground up, no matter what the product, the process will increase the mana of the Hawaiian nation.

[1] Noʻeau Peralto introduced me to this ʻōlelo noʻeau, and the translation is his. Original source: “Kaao Hooniua Puuwai No Ka-Miki,” Ka Hoku o Hawaii, Sept. 21, 1916.

[2] Mahalo to Professor Miriam Jorgensen and Professor Alison Vivian. An early version of this post was produced in response to their course on Constitutions of Indigenous Nations, University of Arizona, January 2016.

[3] For more information about online tools for increasing civic participation and for fostering participatory democracy, see http://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/tech4labs-issue-3-digital-tools-participatory-democracy?

Reblogged this on theumiverse and commented:

A very thoughtful piece from Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua.

LikeLike